Geneva, a great international town, these days hosts an UNECE conference «The way forward in poverty measurement». The event brings together a big group of statisticians to discuss the way forward in measurement of poverty. The programme is packed with quite interesting presentations from countries: «Multidimensional poverty and social isolation in Poland», «Providing international comparability of poverty assessments: experience and problems», «Within subjective poverty, multidimensional poverty and food security: a glance at the living conditions of households and children in Colombia»; as well as from international organizations: «The OECD approach to measure and monitor income poverty across countries», «World Bank Poverty Monitoring in Europe and Central Asia: High frequency data», «The measurement of poverty and social inclusion in the EU: achievements and further improvements (Eurostat)»

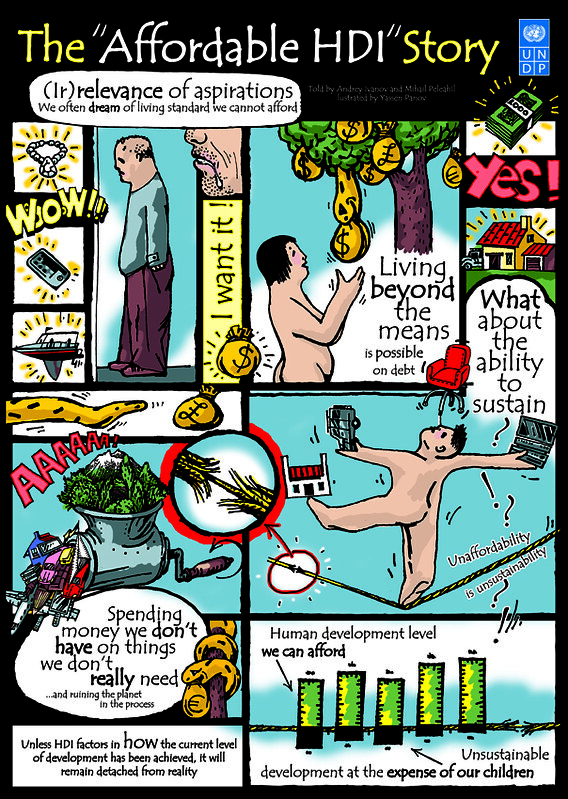

We will present out cutting edge work on data, three big blocks: (i) Capturing Intersecting Inequalities—Social Exclusion Index; (ii) Development that Lasts—Affordable Human Development Index; and (iii) Getting the best out of qualitative and quantitative data—micronarratives. all three are departing from the basic starting point-current poverty measures (however perfect and sophisticated they are) do not capture certain important things, like how sustainable and affordable is achieved development level? what are inequalities, and more important-intersecting inequalities-in our society? what stands behind certain numbers, can we get stories behind the figures?

Monday, 2 December 2013

Sunday, 17 November 2013

Innovative measurements: combining creativity with solid methodological ground

Last week I attended a training “Making an Impact with National Human Development Reporting”, organized by HDRO and BRC in Almaty. This was a great event, which brought together many people professionally dealing with measuring unmeasurable. I was speaking about tough job of combining creativity with solid methodological ground. The presentation outlines main methodological questions, which forms the solid background for creative measurement of issues, related to sustainable human development. The presentation included practical examples from Kyrgyzstan Local HDI and Municipal Capacity Index, Social Exclusion Index used for countries in region, Armenia Affordable Human Development Index proposal and 'Micronarratives' approach with examples from Montenegro.

Friday, 25 October 2013

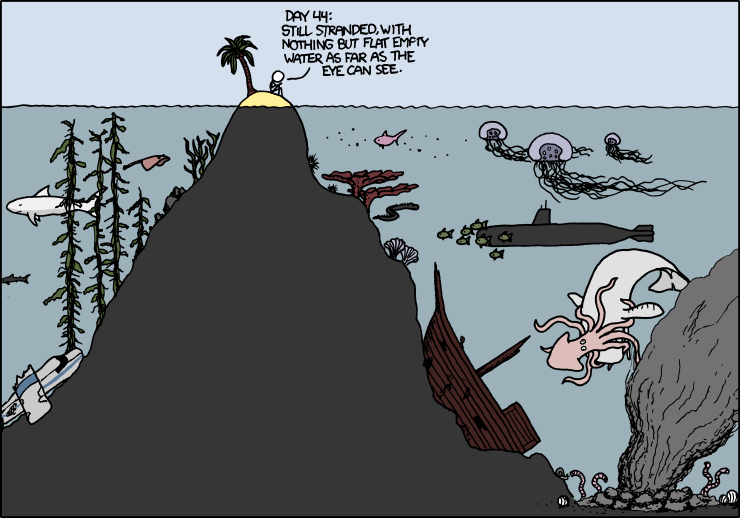

On a deserted, wave-swept shore, He stood – in his mind great thoughts grow

While sitting on a beautiful hill and overlooking the tranquil expanse of water, it is difficult to notice the pulse of life there, in the depths. Sometimes on the surface appear ripple-like patterns from whales’ tails or submarine periscopes, which could provide only a sketchy idea of the life in depths. Over time, scientists have created a number of tools to explore the depths, which fall into one of two large groups. In the first case, we catch a particular instance from the abysmal depths and study it in details. However, we do not care how numerous are such specimens, how they interact in the ecosystem and so on. In the second case, we consider the system as a whole — we track shoals of fish, water flow or distribution of volcanic emissions. In that case, we care little to none what happens to specific instances, we are interested in macro-phenomena.

In the social sciences, we use exactly the same tools — roughly speaking, case studies and statistics, each having their own pros and cons. Case studies (focus groups, in-depth interviews and other similar methods) allow looking deeper into the problem, describing it in detail and in colors, highlighting some features that are difficult to see otherwise. However, such stories are not representative, and reflect the particular specific case. We have too many variables in our society, and it is too hard to pick a «typical representative» (try to find «a typical representative of your country» or «a typical country in Central Asia»), and there is no guarantee that that his or her experience would be typical.

On the other hand, namely statistics, operating with large numbers, can highlight the typical cases, trends and other average values, by which you can judge a society as a whole. The trouble is that most of these indicators gives an understanding of underwater life, roughly speaking, by ripple-like patterns from whales’ tails or submarine periscopes. Razor of research hypotheses completely cuts out the flesh of meaning from the bones of numbers.

There are numerous and repeated attempts to befriend a variety of tools that would give us understanding what’s going on in the depths of society. For example, the article «Managing Yourself: Zoom In, Zoom Out», published in the Harvard Business Review, offers a very simple approach — zoom in or out of the problem as a map in Google Maps. When the map is zoomed out, one can see the mountain ridges, state borders and big highways. When the map is zoomed in, these are dropped out of sight, but one can distinguish individual neighborhoods, streets, and houses. At zoom out one can see the problem in context, while zooming in allow to see important details that are blurred in zoom out.

Cognitive Edge offers a similar tool, which brings together stories, «micro-narratives» and the

|

| Mapping of a sample of stories from the referenced critical incidents project on one of the triad questions used in the project (US Pat. 8,031,201). |

This combination is very useful — politicians and decision makers rarely hear the voice of the people, relying on public opinion studies, and other average values. Using this tool allow one, sitting on the hill, to observe the beat of life at all stages of program or project — analysis, design , implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

This article is also available in Russian.

Original article at my site. This article is also featured in Voices from Eurasia.

Friday, 6 September 2013

Tuesday, 30 July 2013

When Nature Helps Scientists

Human history and societies left many question open—why Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which share the very same island of Hispaniola, are so radically different in their level of development? Why expansion of Western Territories in USA in 19th century was so explosive? Is it unique? What condition level of political development in Polynesian societies? How slave trade has affected long-term development perspectives of Africa?

Human history and societies left many question open—why Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which share the very same island of Hispaniola, are so radically different in their level of development? Why expansion of Western Territories in USA in 19th century was so explosive? Is it unique? What condition level of political development in Polynesian societies? How slave trade has affected long-term development perspectives of Africa?

Social scientists find themselves in disadvantaged position, comparing to natural scientists, physicians, or chemists—they have no luxury to run a controlled laboratory experiments, often considered to be the hallmark of the scientific method. On the one hand, they often deal with past. On the other hand, even if they could design such an experiment, it would be immoral and illegal. To make things even worse, social phenomena often are hard to measure (for instance, what are the measures for “happiness”, “development” or “stability”?) and involve many variables, which affect outcome. (Back in 1987 Jared Diamond wrote an excellent article “Soft sciences are often harder than hard sciences”, where he touch upon some of the issues).

However, Mother Nature often times offers her helping hand, in the form of “natural experiments”—serendipitous situations, when systems or groups are similar in many respects, but are affected differently by a treatment, random or quasi-random. This allows comparing two systems or groups and studying influence of the treatment factor. “Natural Experiments of History” is a collection of eight comparative studies drawn from history, archeology, business studies, economics, economic history, geography, and political science.

Book is easy to read and it is extremely thought-provoking. It offers broad sample of approaches to comparative history, using range of methods—from nonquantitative to statistical, range of compared subjects—from two in development Hispaniola island case to 233 areas in India, range of temporal comparisons—from past to contemporary societies, and wide geographic coverage. Behind all cases there is one simple idea—comparative analysis of natural experiments can be applied to the messy realities of human history, politics, culture, economics and the environment.

Short summary of all chapters is available on-line . Many chapters in this book are based on research papers, which could provide additional information about research methods used.

Labels:

book,

comparative study,

review

Location:

Bratislava, Slovakia

Monday, 11 March 2013

Happy Planet Index

TED Talk with statistician Nic Marks, who asks why we measure a nation's success by its productivity — instead of by the happiness and well-being of its people. Nic presents Happy Planet Index. The index is indeed very simple — it takes people's self-assessment of well-being, life expectancy and divides by environmental footprint. That's all. Next you could calculate index for countries, for group of countries, construct time series... However, the more important than index itself are ideas behind it:

TED Talk, including full transcript.

Report «The Happy Planet Index: 2012 Report. A global index of sustainable well-being»

This post is also available in Russian.

- We do not have a dream, we have nightmares and fear of future. Regular debates about natural resource depletion in particular and a terrible future in general paralyze us, and prevent us acting. (By the way, I do not recall a single movie over the last 15-20 years, which depict future in bright colors. Terminator, The Matrix, 2012, all of them are anti-utopia, about dark and terrible future).

- Our development indicators «measure everything except that it gives life meaning». We calculate the volume of production, GDP and other figures that have little to do with the desires of the people. Moreover, we (both the Government and the private sector) use these figures as a guide for the movement. No wonder we, as a society, get to a completely different point, from where we want to get.

- Good news — some can achieve a good life without destroying the planet. Example: Costa Rica. The average life expectancy is 78.5 years there. According to surveys of the Gallup Institute, residents of Costa Rica are the happiest people of the planet. They live on a quarter of the resources that are commonly used in the western world. 99% of their electricity comes from renewable energy sources.

- The effectiveness of achieving quality of life falls — in recent years the quality of life has improved slightly, but the resources we use to achieve it increased radically. If we want to improve well-being (or at least to maintain the level achieved), we have no other option but to increase the efficiency.

TED Talk, including full transcript.

Report «The Happy Planet Index: 2012 Report. A global index of sustainable well-being»

This post is also available in Russian.

Tuesday, 5 March 2013

I like the environment so much! (Please, don’t ask me to pay for it)

Every morning I open my Facebook news feed and between kitty kitty photos I usually see some pictures attracting my attention to ecological issues, degradation of environment, or articles calling me to ‘go green’. The same situation is in my email box. It seems that global ecological issues caught global attention. The question is what can we do with them?

There are long-standing debates about ‘environmental Kuznets curve’, which suggest inverted U-shaped relationship between development and environment—environmental degradation tends to get worse as economy grows, until some income level is reached and the trend is reverted, as countries start valuing clean environment and have money to invest in it. However, attempts to find environmental Kuznets curve in vivo did not bring conclusive results.

World Values Survey is a multinational poll, asking people about their values and attitudes toward different issues. Survey conducted in waves and we used most recent, 2005-2008 wave. Among other questions, it asked people what is more important for them—economic growth or protecting environment? People also responded if they are ready to give a part of their income for environment protection. We also complemented these perception data with GDP per capita numbers from WorldBank database.

First results were not surprising—the share of those who prefer protecting environment over economic growth had positive correlation with income level. In other words, the richer is a country, the more attention people tend to pay to environmental protection. (Of course, correlation does not imply causality). That the sort of things we expected. However, distribution seems to be rather ‘flat’ and, moreover, there is huge split among rich countries in their growth vs environment attitude. By the way, the picture is for more economically cheerful period of 2005-2008. With economic crisis hitting countries, especially developed ones, attention could gravitate from environmental protection toward economic growth.

However, if we plot desire to give part of income for environmental protection against income level, we will find negative correlations. In other words, the richer is a country, the less desire have people to pay for environmental protection. (Again, this is correlation, not causality.) This finding is quite striking for me. I could see two reasons for this. First, the majority of people in richer (or more developed) countries do not face immediate impact of environmental problems, due to higher urbanization and bigger share of industry and services in economy. In richer country ‘deforestation’ could mean lack of nice parks for a walk. In less developed country deforestation could mean lack of fuel to cook and products to maintain livelihood. Second, more developed countries typically have stronger governance and higher taxation, consequently expectations could be that the Government should sort out environment issues without additional contributions.

The picture gets even more intriguing if we look on preferring environment over economic growth and desire to pay for it—it seems that there is no correlation at all between them. In other words, people seem to like environment, however expect that someone else would pay for it.

Clicking ‘Like’ on yet another Save the Planet picture doesn’t make much sense. The big issue is how to include environmental concerns into a bigger economic picture and how to finance environment protection? On a personal level I switched to public transport, walking to work, and double side printing. What could we offer for societies at large?

This blog post is also available in Russian.

Original article at my site.

There are long-standing debates about ‘environmental Kuznets curve’, which suggest inverted U-shaped relationship between development and environment—environmental degradation tends to get worse as economy grows, until some income level is reached and the trend is reverted, as countries start valuing clean environment and have money to invest in it. However, attempts to find environmental Kuznets curve in vivo did not bring conclusive results.

World Values Survey is a multinational poll, asking people about their values and attitudes toward different issues. Survey conducted in waves and we used most recent, 2005-2008 wave. Among other questions, it asked people what is more important for them—economic growth or protecting environment? People also responded if they are ready to give a part of their income for environment protection. We also complemented these perception data with GDP per capita numbers from WorldBank database.

First results were not surprising—the share of those who prefer protecting environment over economic growth had positive correlation with income level. In other words, the richer is a country, the more attention people tend to pay to environmental protection. (Of course, correlation does not imply causality). That the sort of things we expected. However, distribution seems to be rather ‘flat’ and, moreover, there is huge split among rich countries in their growth vs environment attitude. By the way, the picture is for more economically cheerful period of 2005-2008. With economic crisis hitting countries, especially developed ones, attention could gravitate from environmental protection toward economic growth.

However, if we plot desire to give part of income for environmental protection against income level, we will find negative correlations. In other words, the richer is a country, the less desire have people to pay for environmental protection. (Again, this is correlation, not causality.) This finding is quite striking for me. I could see two reasons for this. First, the majority of people in richer (or more developed) countries do not face immediate impact of environmental problems, due to higher urbanization and bigger share of industry and services in economy. In richer country ‘deforestation’ could mean lack of nice parks for a walk. In less developed country deforestation could mean lack of fuel to cook and products to maintain livelihood. Second, more developed countries typically have stronger governance and higher taxation, consequently expectations could be that the Government should sort out environment issues without additional contributions.

The picture gets even more intriguing if we look on preferring environment over economic growth and desire to pay for it—it seems that there is no correlation at all between them. In other words, people seem to like environment, however expect that someone else would pay for it.

Clicking ‘Like’ on yet another Save the Planet picture doesn’t make much sense. The big issue is how to include environmental concerns into a bigger economic picture and how to finance environment protection? On a personal level I switched to public transport, walking to work, and double side printing. What could we offer for societies at large?

This blog post is also available in Russian.

Original article at my site.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)